“], “filter”: { “nextExceptions”: “img, blockquote, div”, “nextContainsExceptions”: “img, blockquote, a.btn, a.o-button”} }”>

Heading out the door? Read this article on the new Outside+ app available now on iOS devices for members!

>”,”name”:”in-content-cta”,”type”:”link”}}”>Download the app.

You can read the full tribute to Climbers We Lost in 2024 here.

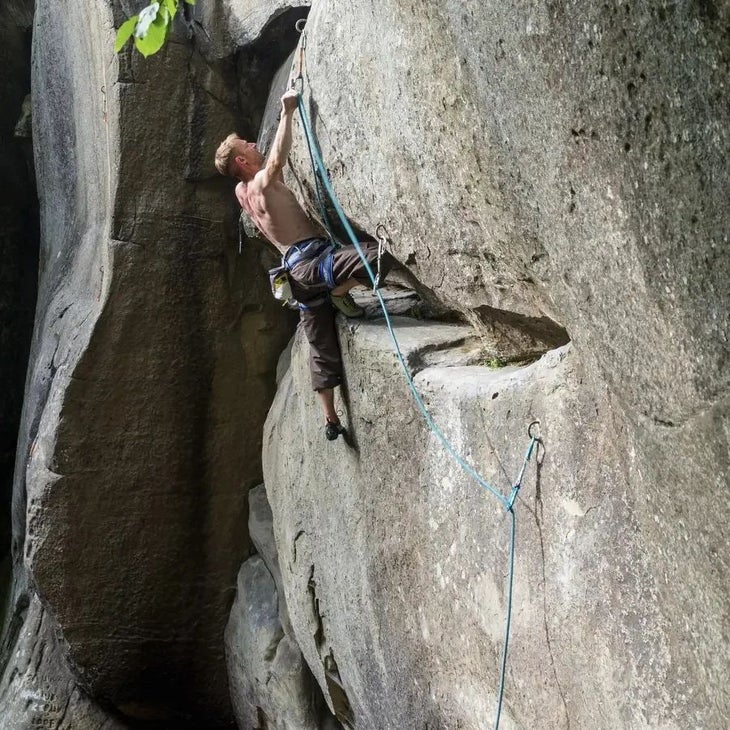

Ukrainian rock climber Maksym Petrenko, 46, died on October 15. He was serving with the Ukrainian Armed Forces to repel Russia’s invasion of his home country, when he was struck by mortar fire amid the ongoing battle for Toretsk.

Born in Luhansk in 1978, Petrenko was among the strongest climbers to come out of Eastern Europe in the early days of competition climbing. He was a fixture on the international competition circuit throughout the 1990s and early 2000s, competing in 41 IFSC World Cups and seven World Championships. Petrenko won gold at Youth World Championships in 1997, and podiumed five times on the Open circuit. He redpointed 5.14c outdoors when 5.15a was the world’s hardest grade, and remains the only Ukrainian to win a Lead World Championship medal (1999).

Dutch climber Jorg Verhoeven met Petrenko while training in Innsbruck in the early 2000s, and competed with him on the the close-knit comp circuit of the time. Verhoeven described a fiendishly strong climber who, unlike Western European climbers like himself, had little to no financial and logistical support and scant training infrastructure at home in Ukraine, but managed to bootstrap his way through competitions.

The competitive rock scene at the time was far more intimate than today’s far-reaching World Cup circuit. “He was kind of an outsider,” Verhoeven said. “There was a small group of Ukrainians and Russians who might attend these comps, but it was always just a couple of people. As a Dutch climber, I was kind of by myself, too, so we became friends.” Verhoeven said Petrenko was something of an introvert, “but when you broke through that barrier you could see a caring person, and an incredibly psyched climber. He always found his joy in life through climbing.”

Verhoeven, and several others who spoke with Climbing, said Petrenko was an “crazy” climber, driven on a level nearly unfathomable to his Western contemporaries. “These climbers from Russia, Ukraine, they had a totally different mentality,” Verhoeven said. “The French guys, Austrian guys, even me, we were financed by our federations. You train in a nice facility, you travel by plane to the comps, you win or lose, and you go home. It’s hard, but it’s easy, really.”

“Then you come across some people, and they fight on a different level,” he continued. “They train in a nonexistent gym. They basically have a pullup bar and maybe some shit holds. That’s it. They drive 10,000 kilometers alone just to reach a competition. Maksym was that guy. He wanted it.”

Professional Ukrainian climber Jenya Kazbekova, daughter of former pros Serik Kasbekova and Nataliia Perlova, recalled childhood memories of traveling with her parents and Petrekno to compete. “He was very strong and hard working,” she said. “The amount of training that he was doing at the time, it was shocking to generations of climbers afterwards.”

This was echoed by fellow Ukrainian-American pro Vadim Vinokur, another close friend, who immigrated to the U.S. in his youth but kept in touch with Petrenko and competed with him at many of the IFSC comps of the era. “This was the 1990s, just a few years after the dissolution of the Soviet Union,” Vinokur explained. “The country was a mess, most people there were just trying to figure out how to survive. For Maksym to be able to train—and not just well enough to get participation trophies, but to perform at such a level as to stand on the podium—it’s difficult to emphasize how impressive that was.”

He recalled a time when Petrenko, climbing in Céüse off one of the typically sparse guidebooks of the era, fired up a two-pitch 5.13c—the wrong route, he’d meant to tie into a 5.12d—without enough quickdraws. Halfway through the second pitch, Petrenko realized that he didn’t have nearly enough gear. Without a fuss, he downclimbed partway, pulled some of his draws off the lower section, then climbed back up—managing to onsight the climb. “In 1999, onsighting 5.13c? That’s a big deal,” Vinokur said. In his typical understated fashion, Petrenko lowered and told his friend, “Huh, I guess that was a pretty hard 12d!” (Another climber nearby came up and informed the pair of their error.)

His endeavors post-climbing were less successful. Petrenko’s house and belongings in Luhansk were taken by separatists from the Russian-backed Luhansk People’s Republic in 2014. “They came and told him, ‘This house is not yours anymore. If you don’t want to be a separatist, we are taking everything,’” Verhoeven explained. This experience seemed to catalyze a downward spiral for Petrenko, one he was never fully able to pull out of.

Vinokur and Verhoeven said Petrenko lived an itinerant life from this point, bouncing between family in Ukraine and friends in the West, pursuing jobs as a routesetter and coach. Petrenko periodically stayed at Verhoeven’s apartment in Innsbruck, and with other routesetter friends off and on, but he struggled to hold down a job. “Many gyms, I guess it was too much for them to handle the logistics of hiring a foreigner, particularly someone from Ukraine,” said Verhoeven.

At this point—before Russia’s full-scale invasion in 2022—it was not easy for Ukrainians, as non-EU members, to get permission to work in the West. Petrenko had to dodge visa restrictions and work under the table, and most gyms didn’t want the hassle. “Once the invasion happened, Ukrainians were given more accommodations and lenience as refugees,” Vinokur explained, “but before 2022, it was quite hard.”

Petrenko also tried to start a company manufacturing climbing holds, but never managed to get it off the ground. Verhoeven could tell his friend was battling depression, but he struggled to help him. “It was hard to see,” Verhoeven said. “We were friends, but we weren’t such close friends that he would share his struggles with me. When he stayed with me, he wasn’t sleeping, his behavior was chaotic. Every day he would say something different. He would say, ‘No, I’m fine,’ but I could tell he wasn’t.”

Vinokur, who was also in touch with Petrenko during these years, said his friend had always had a hard time finding a life outside of climbing, but this was severely exacerbated after he lost his home in 2014. “He was trying to transition from being a truly exceptional climber into something else,” Vinokur said, “and when the Donbas war started, everything he was working on just fell apart.”

When Russia’s full-scale invasion began in 2022, Petrenko was at home with family in Ukraine. As a military-aged male, he was forbidden from leaving the country. After being mobilized in early August of 2024, he told Vinokur he would receive a month’s training before being sent to the front. Vinokur’s descriptions of speaking with his friend on the phone in his last weeks are hard to stomach. He was afraid, Vinokur said, but he also sounded “resigned to die.”

“He was asking me a lot when I thought the war would end, and if people in the U.S. were still thinking about the war,” Vinokur added. “But I don’t think many people here are really paying attention anymore.”

Scarcely a month after Petrenko finished his training, he’d been killed near Toretsk.

Vinokur said it would be a disservice to his friend’s memory to paint him as a gung-ho patriot, thrilled to go into combat against the Russians—something that Verhoeven echoed: “I could never imagine Maksym fighting in a war.” “But all the Ukrainians who volunteered to fight,” Vinokur added, “those really motivated people, they’re gone now. The war has turned into a meat grinder.”

While Petrenko may not have been excited to take up arms, he was clearly no coward. “There are Ukrainian men who try to escape the country, they pay coyotes to cross the border into Poland, Romania,” Vinokur said. “It can surely be done. But Maksym stayed, realizing he could be called up to fight.”

“And when he was called, he went. That means something.”

Maksym Petrenko is not the first Ukrainian climber to trade rope for rifle. He joins a tragically long list of Ukrainian alpinists, mountaineers, and rock climbers who have died in combat fighting to defend their country (Ukrainian Climbers We Lost). He is survived by two brothers, a sister, and a daughter, who lives in the Czech Republic.

You can read the full tribute to Climbers We Lost in 2024 here.